Mining the Red Wheelbarrow

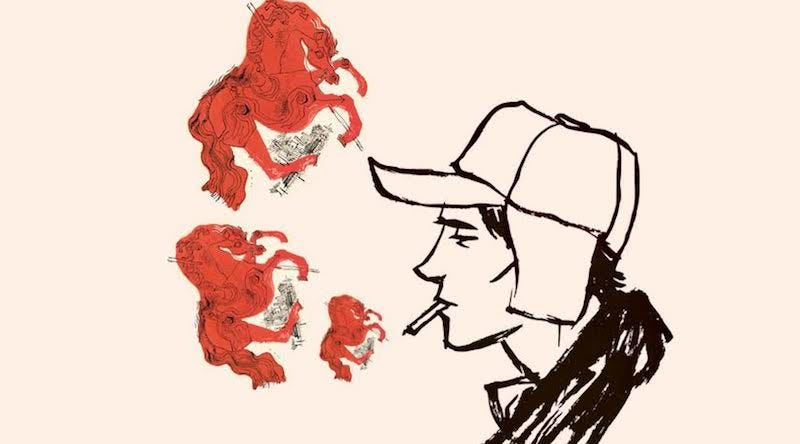

"I shoot people in this hat."

so much depends

upona red wheel

barrowglazed with rain

waterbeside the white

chickens

—The Red Wheelbarrow, William Carlos Williams

When I was little, my grandfather made skeletons dance by turning on the stereo. Up to the age of ten, I had been a popstar, an architect, an egyptologist, and an astronaut. By the age of five, I had felt the crunch of sand between my teeth, the pillow of play dough, and the satisfying peeling of dry skin. Even earlier I recognised my aversion to loud noises of all kinds: balloons popping, fireworks, dogs barking, party poppers, and other explosives. Coming to life is a mission to sensory stars.

As we grow, we misremember the beauty in sense, often mistaking the curation of sensory memories for materialism. The self-help books tell us to “throw out what you don’t need,” but would you collect something you don’t require in some way? One March, I took a red nose (for the comic relief charity) and wrapped it in lots of sellotape. This made the ball now bounce. I kept it on my bedside table for months. How fascinating that such a non-object became the picture of intrigue. When my mum sent me to school, she would put strawberry perfume oil on my sleeves so I’d think of her when I felt depressed. Just as prisoners decorate their cells with personal belongings, a house is furnished with the unique perfume of its inhabitor(s). There were two sisters who lived on my street, and whenever I’d knock on to ask if they could play out, the bouquet of their living environment would hit me. It was totally unique to their house, and it’s not often you feel a stranger to a scent, but one does when faced with something you cannot call your own.

In Krzysztof Kieślowski’s 1991 film, The Double Life of Veroniqué, Weronika frequently carries a clear bouncy ball with colourful stars suspended inside, sparing moments to gaze through it. Through the object, she sees the world inverted. At the start of the feature, a young Weronika counts stars in the sky with her mother. Further scenes show the characters questioning the nature of existence. The significance of this little ball is to reinforce the theme of parallel worlds. J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye sees Holden Caulfield don a red hunting hat. While this seems self-explanatory, the importance of this object extends farther. Holden feels alienated from the rest of society, so in wearing the hat, he identifies himself as something other. In the novel, he says, “‘This is a people shooting hat," I said. ‘I shoot people in this hat.” These objects shape the personalities of their respective characters—acting as a kind of umbilical cord between them and the outside world.

As a poet, objects play a large role in writing a poem. I know for myself that choosing abstract and concrete imagery opens the senses, enabling my readers to touch what I touch, see what I see, etc. For example, Sylvia Plath uses various objects that recur throughout her breadth of work, such as balloons, gold jewellery, and conch shells. To increase the significance of an item is to give a part of yourself to it, like a bride choosing a perfume for her wedding day. As a child, I found a white pebble with a pink streak wrapped around it. For an outsider, it was just a pebble, but for me it represented fantastical worlds. This little rock had the power to open up the third eye.

One must ask the question: How is clutter defined? When Tutankhamun’s tomb was discovered, so was an ivory board game called Senet. It can be assumed that the pharaoh enjoyed playing this game when he was alive, thus giving us another example of object significance. Marie Kondo’s book, Spark Joy, asks the reader to consider the items around them and ask if they “spark joy”. The conflict in this idea is the potential for all items to feel necessary. This is one of the many unresolvable questions we can ask ourselves. As the saying goes, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”

In a society ruled by capitalism, the acquisition of objects is a common one. Who are we without our possessions? If you had everything taken from you tomorrow, would your identity be called into question? I wonder if the curation of objects could be considered a survival instinct. When we enter this world, we seek out comfort and experiences to please us. If you were christened, you might have a silver spoon somewhere. I was given my late Grandma’s bible at three-years old. It is my view that personal belongings do not factor into materialism, and while it is often argued that humans choose objects over spiritual pursuits, there is a possibility to connect the two. Consider them as babies and the myths you imbue as a placenta. The conversation surrounding overconsumption is certainly valid in some aspects, but stripping ourselves back to natural form, we have never been without the personal touch. Among artefacts uncovered, you will find a variety of handmade jewelry pieces. In the end, when our time comes, our impact on the lives of others is what will be remembered foremost, but our loved ones will cry at old Christmas cards and shell necklaces we may have made in nursery.

I’ve kept many things in my life. The ones that turned out to be most important seem to have escaped. Does life conspire? Can we imagine a life that doesn’t? Thanks for sharing your lovely thoughts.

I love this so much 😭 i keep many things just for the sake of sentiment and attaching memories to things is like breathing to me. My clutter and inventory may not define me, but they certainly reflect me. Thank you for writing this!