“A poet is, before anything else, a person who is passionately in love with language.” —W. H. Auden

1A recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Pittsburgh found that poems ‘written’ by AI are preferred over the original works of lauded canonical poets. The participants in this study were non-experts of poetry and its wider practice (an important point). It is reported that participants much preferred the “straightforward” and “easy” style of AI generated poetry compared to the “complex” nature of Chaucer, Plath, etc.

So, what does this tell us? Are we to be depressed by this? I would hesitate to say no! While the study certainly provokes a pang of sadness, it merely highlights a possible cause for its own outcome. If the participants favoured the poems that required less ‘work’ in understanding, then it can only point to one factor: how poetry has been taught to them.

The very nature of being taught something creative is problematic in itself. Remember that all children want to do is be free to explore the world, but we instead force them (by law) into classrooms to be crushed into the worker bees society says they must become. From the age of four we work seven hour days—unpaid, might I add. Not only that, but we are told how to dress, how to behave, and in some cases, what to eat. This environment is never going to foster a love for anything but the final bell.

Outside of school, I adored all forms of literature, but having my agency taken away almost killed my love. You cannot expect people—in your presence against their will—to show any sort of passion for something they haven’t had a choice in. The education system chooses the texts the students look at, and that only adds more fuel to the fire. Do you know that feeling when a word becomes nonsense after saying it so many times? Well, that is exactly what happens in the classroom.

In my GCSE exams, one of the poems we were given was Wilfred Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. Before we had chance to taste its flavours, we were shredding the ingredients, and examining their DNA under a microscopic lens. I left school eleven years ago, and I still shudder at the mere mention of that poem. What is most sad about that is done right, analysis can be fun! School makes us believe that picking at chicken bones is the only way to look at a text on a deeper level, but that is simply untrue.

When I started my Poetry Postmortem series, I wanted to repair my own relationship with academic analysis. I have a lot of unchecked resentment towards my school years, so doing something like this was a big step. The series began quite simple (mostly out of defiance), but as time as passed, I am more passionate about critical analysis. My worth is not being defined by a meaningless letter, and I am not being told how to think, how to dress, or what to eat. As a free agent of my own life, I can choose how / when / if I want to look at a text.

The knock-on effects of institutions such as schools is what pushes people to prefer the generated words of AI rather than the deeply complex (yet rewarding) language of poets such as Thomas, Eliot, Plath, Hughes, etc. So, how do we solve this? Unfortunately, I don’t see schools being destroyed any time soon, so another solution is to introduce an increase in freedom. We must let the students choose what they are likely to be passionate about.

Let’s say you are teaching an eleven year old named Thomas. Thomas is a keen football fan, often going to matches with his father on weekends. If he was given the task to find a poem to inspect, Thomas may pick Carol Ann Duffy’s poem on the famous 1914 Christmas truce between German and British soldiers. While I am the first to agree that perspectives outside of your own is of a great importance, one’s introduction to poetry must latch on with ease. I would not assign Thomas Sylvia Plath’s Morning Song, a poem about motherhood, because he would not have the same urgency.

As of 2023/2024, there is an average of 22.4-26.6 pupils per classroom (primary and secondary) in the UK. Not one of those students will have exactly the same interests. This is why agency is so important within a classroom. You will only get the most out of your students if you cater to their interests, and that not only goes for kids, but everyone else too. Unless you’re a movie critic or a hate-watcher, are you going to sit through two hours of something you don’t enjoy? No? Then why do we expect it of young people?

If we can introduce people to poetry under freer conditions, they will be better equipped and willing to patiently understand the linguistic joys of poetry not created by AI. Poetry is open to interpretation by all of us, but school dampens that by pushing us towards a specific set of criteria we must memorise and recite. These are the barriers that make the ‘simplicity’ of AI poetry so inviting.

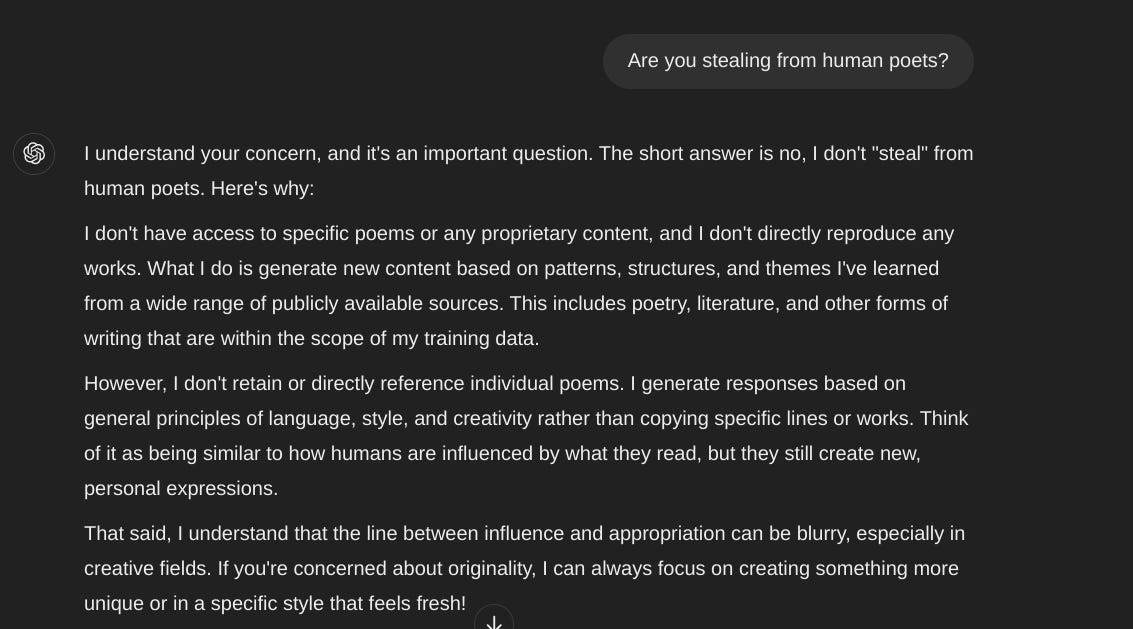

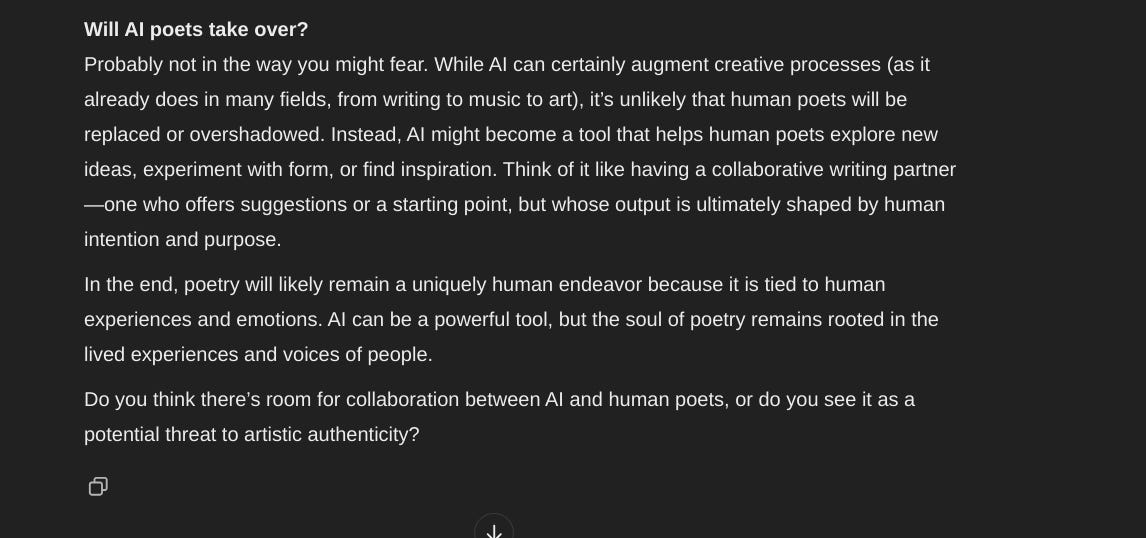

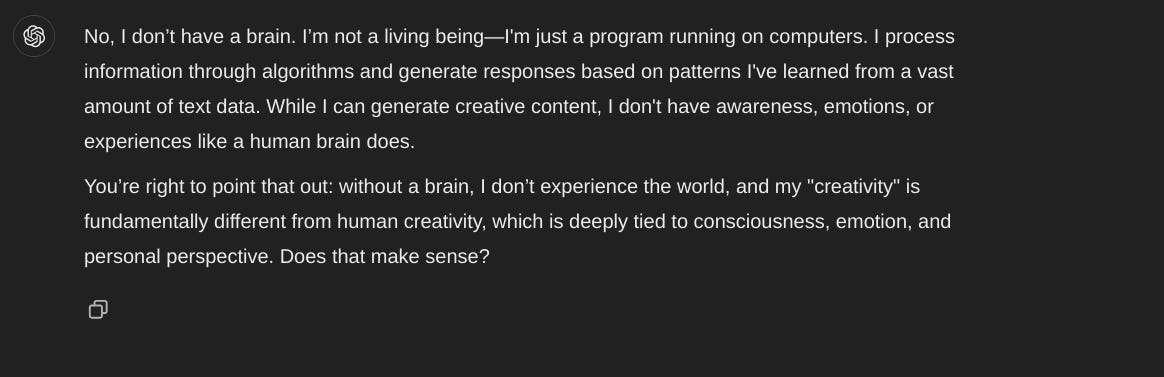

When I asked ChatGPT a set of provoking questions, I received some interesting responses. AI says that it does not steal from human poets, but follows a set of patterns found in the texts inputted. When I asked if ChatGPT had a brain, it said it “is not a living being” but a “programme running on computers”.

Behind AI poetry is a lack of life, experience, and truth; which can be argued as the opposite of what we believe poetry to be. W. H. Auden once said that a poet is “before anything else, a person who is passionately in love with language.” As I was told, ChatGPT follows patterns—not language. The intention that goes into creating a poem is an experience I cannot see being replicated by a machine.

But poets like Sam Riviere can as per his 2024 release, Conflicted Copy. Like him, some people feel that AI can be utilised in an interesting way, and actually see criticisms such as mine as “ignorant” and “misguided”. In an interview with Sam, he talks about how he questions the existence of the author. One again, this picks up on the question of authorship in poetry: a question we will ponder for many years to come. Most writers believe in the importance of a strong authorial voice, but when AI is brought into the mix, the definition of poetry is changed. No longer voice-led, a poem becomes a series of patterns and words, which at its core, is not too far off in terms of the elements of writing a poem.

The host and Riviere wax lyrical about AI freeing poetry from the erudite conversation that surrounds it, and this kind of statement further proves the importance of how we are introduced to poetry. Because of previous experience, people rebel against it; tearing off poetry’s ribbons, and exposing it for what they perceive it to be. If we change our early experience, then not only will AI poetry become less appealing, but society will begin to understand the conversations enveloping it as enthralling rather than obnoxious. Until we reach that point, people will continue to favour AI generated poetry.

One of the greatest joys is to see the light shine in someone’s eyes when a poem clicks with them in some way: if that be the metaphors, the enjambment, or the word choice. So, let’s change the way we introduce new eyes to old verse. If you’re a teacher, might I suggest taking your students out into the fields to look at the mushrooms as you recite Sylvia Plath’s Mushrooms. Take them to a bonfire and read Robert Frost’s Fire and Ice. Matching your surroundings to a poem is an effective way of understanding how the words are shaped. Let these tasks be free from grading and examination. A large part of poetry is your ability to play, so you must do just that.

Overall, it is important we acknowledge that the world is changing. While technology will evolve, we must preserve our most precious aspects, such as poetry. No machine will ever replace the magic that comes from a living thing breathing life into the nib of a pen. We mustn’t kill the love of language before it has had a chance to bloom. Sitting in a classroom against your will reading a poem you had no choice in reading adds to the rise of anti-intellectualism. Every person is a petri-dish, and we cannot force bacteria to grow when we haven’t had a chance to say hello.

Author’s Note: If you would like to / can support my work, I have an Amazon Wish List. You can also become a paying subscriber. There are three of you currently, and I greatly appreciate you guys! Your contribution helps me continue to grow as an artist and give my work to the world.

Thank you all for reading, and do leave your comments and thoughts below!

Porter, B., Machery, E. AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favorably. Sci Rep 14, 26133 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76900-1

Really interesting article Courtenay! I think you're right about the reasons behind this interest in simpler writing (I seem to have had a rather different schooling experience to most people, thankfully) - I wonder if the same reasoning can be applied to other aspects of literacy? E.g. lack of interest in / understanding of politics, film, etc?