C: Monica, I wanted to begin by asking you what age you were when you started writing?

I was twenty-five when I met author Tom Spanbauer, author of the novel Faraway Places, a beautiful, compressed novel. Since then, he's written additional books. I became known as his first student—which is awesome. There were other students in the initial workshop, of course, but they dropped away and more joined.

soon joined the workshop, as did Suzy Vitello, and others. We all studied with Tom as he developed his approach and his particular lexicon, "Dangerous Writers." Tom Spanbauer really turned the key and showed me—perhaps showed us all—ways in which writing can be a serious and rich undertaking. When I met him, he told us that he was HIV positive. He wanted to write his stories before he died. There was such an urgency and significance to it all. The way he said it made writing an essential part of being human. That's the moment I really started writing.C: You are friends with plenty of famous writers. Would you say you are similar in terms of how you approach writing?

If you mean, specifically, authors like

, Lidia Yuknavitch and , I'd say we all have very different writing styles, but we spent years in our own workshop together, supporting each other's process, so we have some similar terminology and a common understanding. Chuck and I met back in Tom Spabauer's workshop, decades ago, before either of us had a book out. I left for grad school, and by the time I came back he'd published Fight Club (his breakout blockbuster). I met Lidia Yuknavitch after grad school, and it's been amazing to watch her soar. She is a star! joined us later—after we'd left Tom's workshop and founded our own, with author Suzy Vitello often hosting and holding us all together, organizing logistics and sending out the weekly email, asking "who's got pages?"—and we were honoured to see Cheryl’s breakout memoir Wild first as a draft, then a success. But as writers, we all have our individual vision, values and aesthetics.I'm grateful to be friends with a wide range of authors, coming from all different backgrounds and routes to writing. That's part of the amazing thing about having a book out in the world, contributing one's voice to the larger conversation: you get to meet cool people.

C: Your book, Clown Girl, reminds me of Heinrich Böll’s book, The Clown. Was there a particular inspiration for this book?

The inspiration came from my own life, initially. I worked as a clown in the late 1980's. Somebody needed clowns, and they put the word out. I raised my hand. I wasn't a professionally trained clown, but I'd studied dance and theater arts. I taught myself to juggle, just enough to fill time, look festive, signal clown-ness and catch an eye. When a routine flopped, I could start juggling and get out of the situation. I'd learned a few makeup tricks by volunteering to put makeup on the chorus of the Portland Opera. After the first gig, more work came in. I was hired by a number of corporations to work opening day celebrations, street fairs, food fairs, and various launches. I was a Corporate Clown, and a street clown, and a free-ranging artist earning some scratch.

But the job was a metaphor, really, from the start. It was a way of interacting with capitalist systems from the margins, and seeing labor at its most absurd.

For me, clown work spoke to a very particular and under-recognized form of femininity, and a particular relationship to the feminine overall--not just in a heavy layer of makeup, but also in the routine, and that aspect of entering a crowd knowing that people would stare. Showing up in clown gear gives people permission to gawk, while it also excuses the clown, placing a body outside of traditional gendered expectations. Women are already scrutinized when they enter into a public space. Women's clothing is scrutinized. Their hair is open for comment. Women's body types are always up for grabs, pun intended—if it's even a pun, because I mean that fairly literally. I worked a few different jobs, beyond clown work, and I lived in a sea of strangers and friends, drunks and stalkers, public transit, laundromats and apartments; showing up for work in a public space in full clown gear was both a form of resistance, rebuking feminine ideals like tiny feet and precise makeup, and it was freeing.

There were external elements, to the clown metaphor and physical comedy of labor, too.

Portland set the pace for free speech back in 1987 when strip clubs were legally deemed a form of free speech by the courts. Suddenly, every bar and corner store had the right to display and commodify nakedness. Mostly, it was women on stage and men who owned the clubs, with a few exceptions, like one of the oldest clubs, Mary's. I've never been the kind of woman who would choose to be a stripper. No judgement toward those who do, it's just not my relationship to performance, strangers or my body. But, I am the kind of woman who would show up in a challenging costume. Ha! So one thing that interested me was the number of men who would try to talk to me, a silent clown. Some may have struggled to find their own roles, in witnessing a clown on the street. Stripper? Hooker? Fool? I was none of those things. They had no place in my story, honestly, unless I granted them one.

Once I became a college professor, I felt the clown impulse clinging to my clothes like smoke in an old tavern. I was still a clown, and I was also the authority in the room. Positioning myself as a clown, intellectually, while leading a class, gets at the best aspects of the original anarchists’ ideas, handing power back to students, to the learning process, while still guiding the classroom. It's about creating a non hierarchical space, welcoming mistakes and building in a structure to support moving forward, academically, intellectually and creatively. I don't mean that I wore clown gear to class. I only felt myself in the role. That's when I started writing Clown Girl, when clown work became apparent to me as a working metaphor I carried in my body.

With the internet, of course, there's also been a rise in clown porn, and that relationship between the feminine and male titillation has continued to evolve, like all things under essentially patriarchal structures, but for me, it will always be a way of life, visible or not, and it's a way of resistance, a way of ducking the margins of capitalism, enjoying a bit of freedom and intellectual joy.

Clowning takes on a wider range of forms than many grant consideration. There's a history of the role of the clown in most cultures, one way or another, from tricksters to truth teller, and from the self-styled, as I was, to more professional like Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus school-trained performers, and Cirque du Soleil and other phenomenal physical performers. In Portland, we're fortunate to have "drag clowns," who cross the line into high art. There's one in particular, Carla Rossi, who I just couldn't love more. Anthony Hudson / Carla Rossi (thecarlarossi.com)

C: One might say the writer is a kind of clown, hiding many tricks. Do you think this is true?

Being human is a kind of clown work, to varying degrees. Some say Jesus was a clown, which I think is an awesome lens, and I bring it up because clown work is essentially that of a servant leader, a wise fool, a willing, daring expertly-inexpert voiceless voice. I'm all for it. I'd put the writer in that pool of larger humanity, definitely.

C: You worked with animals when you were younger. Do you think that experience has found its way into your writing, aside from quite literally in The Stud Book.

I worked in Animal Behavior, collecting data on larger, zoo animals, not domesticated animals. I stood in cold, damp rooms through Oregon winters, breathing the heat of animal shit while I recorded who was humping whom or who was playing, eating, fighting....

Patience and observation are definitely writing skills, in my opinion!

C: What is your main goal when it comes to writing?

My goals have shifted over the years, with life experience and other elements. When I first started writing, I loved the magic of the way sentences come together. People talk, and every sentence is a bit of a surprise, in the best moments. Language is incredible. There's a mystery to it and a uniqueness to each speaker, a freedom in diction and syntax. When I started writing, I liked the mysterious edges and the sound of voices, the human struggles and moments of transcendence, and to find the beauty and comedy even in hard knocks.

C: Where do you do most of your writing?

I write at home. I have a space these days. In the beginning, I had a studio apartment and a typewriter. Then a walk-in closet. Now, a room and a laptop.

C: Are there any particular books that made you want to write a certain way?

There are so many books that have inspired me to want to jump into the conversation, to add my voice on the page to the larger, ongoing conversation of literature through centuries, bringing my own words, ideas and images. Writing is a big party that's been going on for centuries, and we're here, now, and we can add our jokes, our hearts, our voices, while reading the words of people who wrote hundreds of years ago, or yesterday, and that's amazing.

C: I know you have a daughter. Do you think that a writer reading bedtime stories has a different effect to a non-writer?

I don't know. I was fortunate that she has always had good taste in books. She picked up Coraline, by Neil Gaiman, when she was so little. She showed me the work of Miyazaki, still a favorite in our house. It's possible I honestly don't quite know what life is like, for a non-writer, now that you ask...

C: A lot of writers want to know how to break through the wall, and they may look at you and see a success story. Do you believe the path to success is free of debris, or is it littered with various locked doors?

Writing is both uniquely accessible and yet so very hard. There's the practice, which is satisfying in itself, putting words on the page, developing stories, going to open mic events, and then there's the career. I spent ten years writing and trying to place my first novel, Clown Girl. I came to see publishing as a fortress, a stone wall. You have to keep circling, looking for the opening, until you find it. Even successful writers still meet with rejection along the way. There are options, like self-publishing or smaller presses, and it's hard to say when each of these is the right answer. A person has to keep making decisions, all along the way.

C: You run a successful writing programme. Would you call yourself a more traditional writer? Are you a rule follower or a rule breaker?

I designed, developed and established the BFA at the Pacific NW College of Art, but left that position during the pandemic. At the same school, I launched and supported a speakers series for Indigenous authors. It was great. That too is behind me, as I've left the college. Now, I teach independently and take on manuscript review projects. I'm steeped in the old Portland way, where we found our education in bars as well as in any classes. I learned at Tom's kitchen table, among other places. We've all learned by working together. I'm not sure about rule breaker or rule follower, because I'm not even sure who is making the rules, around here, if not us.

C: The female experience appears to be very central to a lot of your work, why is that?

That's probably true...perhaps because I am a woman, but even more, because the lives of the women I have known, and my own life experiences, weren't reflected in the media when I was growing up when I starting writing, if they even are now. Most of the characters we knew were written and shaped by men under the value systems of patriarchy. Patriarchal domination makes women into "the other." Women's bodies often become a place to put culturally devalued traits alongside unrealistic expectations. We're supposed to be watching our weight while eating giant hamburgers to show we're not like the other girls, acting neurotic, spending too much money, stirring up catfights and chasing boys—then married and dull and old by fifty. Meanwhile, I was walking alone at night to punk shows at Portland's Satyricon, ("...where Kurt met Courtney"...) in my Doc Martens, enjoying the friendship of amazing, free-thinking women, reading Sartre and Anaïs Nin, refusing to shave and fending off weird dudes by the dozens. I was interested in ideas more than shop-til-you-drop consumerism. I'm not sure we know what a woman is, free of gendered expectations, but I strive to be my own person, in body and mind, living a satisfying life rather than playing the part of a cog for capitalism. I wish everyone, anywhere on the continuum of gender, the same.

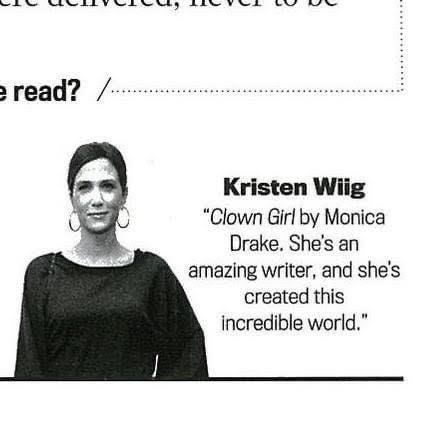

Kristen Wiig has been credited with revolutionizing the rom-com, with Bridesmaids. Before that film, she’d read Clown Girl and bought the film rights. Clown Girl is essentially a dark romantic comedy about a cop and a clown. Bridesmaids also has an officer as the romantic interest. I’m going to go out on a limb and say my work offered some flicker of inspiration toward making that blockbuster? It’s just a thought, but I’m glad to see women’s roles in pop culture evolve—particularly women in comedy.

C: Are there any topics you would like to explore in your work in the future?

I have a range of ideas, things I'm working on. I actually have two personal essay collections, a novel, a short story collection and a memoir all in pieces, and am working to see which comes together, and the material varies, while the lens is still mine, a worldview.

C: If you could pair one cocktail with your books, what would it be?

Definitely a Boulevardier, for the "man about town," Ha! Mine is the work of hanging out and witnessing, sipping the drink of those who walk the city.

C: Many writers don’t believe in writer’s block, but if a writer comes to a stop, how would you advise they get through?

If a writer wants to write but feels they're struggling, I'd suggest horsing around. Take a walk, let yourself think, let your mind roam. When you sit down to write, find a starting point that interests you. The voice might be irreverent. It might take the form of a letter. What might one character write to another? How does a letter shift the point-of-view, and what is cracked open with this switch? Have fun with whatever it is you're trying to say, and get working. A first draft can move in any direction.

C: What is your favourite season? Are you most productive then?

My favorite season these days is whenever the West isn't on fire, when we're not breathing smoke, when the trees I love are living well.

C: Do you think it’s important for a writer to talk to as many people as possible?

That's an interesting question. Perhaps it isn't? But honestly, I don't know.

C: What is a question that keeps you up at night?

Entire nations are resistant to addressing climate change, yet interested in forced birth. Who wants to force more humans to be born onto a dying planet? It's so irrational and short sighted and unkind.

C: Are there any modern writers who stand out to you?

So many! I love Lidia Yuknavitch to the moon and back, and adore her voice on the page! I'm watching the work of Jennifer Robin, because she's wild! I'm a fan of Stephen Graham Jones, always. I love the serious, the supernatural, the sacred and profane, the absurdists and hesitant. If I were to truly start listing, I wouldn't find the end of the list...

C: To finish off, do you have anything on the back-burner? Will we see more from you?

I'm actually working on several projects. More to come, on this! Thanks for asking!

I would personally like to thank Monica for answering these questions. I greatly appreciate her taking the time to do so. Her answers are enlightening, as a writer myself, and I am sure they will prove interesting to all of you.

Congratulations on this piece. Loved the interview!

BTW - I happened to finish up a zoom writing workshop with Monica just last week. It was fun and inspiring. Improved my writing process.